Androgynous Beginnings of Pointe Work

In the earliest days of ballet, only men danced ballet. Ballet began in the French and Italian courts and dance form looked drastically different from what it looks like today. All women characters were performed by boys “en travesty” (young men dressed as women, similar to many roles in Shakespearean plays).

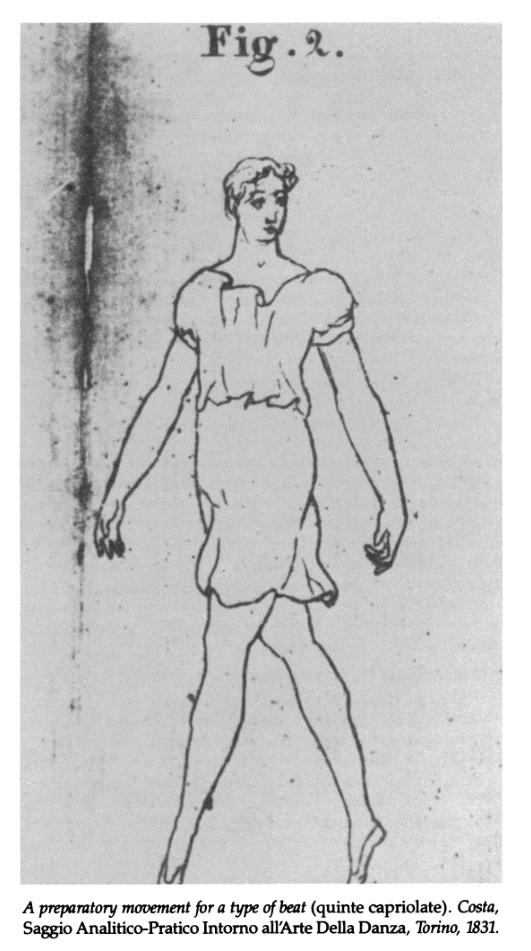

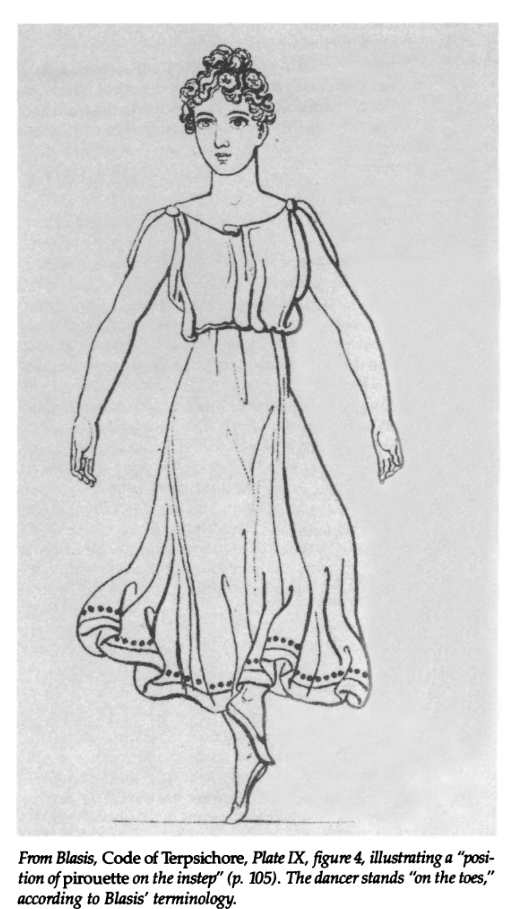

Pointe shoes are the most iconic symbol of ballet. The first evidence of dancers rising on their toes is from the 18th century. Early pointe was distinct from the modern technique in a few ways: dancers did not rise fully onto the very tips of their toes, their shoes were not reinforced or supportive like modern pointe shoes, and both male and female dancers trained in the technique. Sandra Noll Hammond goes so far as to say that only “after 1779, that image became a female on pointe”. This indicates that, at the time, pointe work was not gendered or exclusive to women. Men training to rise “sur les pointes” in the 18th century wasn’t intended to break gender norms, but it is very different from modern ideas about pointe work and femininity.

Gender Subversion and Women in Ballet

Although ballet was dominated by men for the first century, women were not completely uninvolved. A dancer named Marie Camargo was described by Voltaire in 1726 as “dancing like a man” because she was the first woman to complete an entrechat quatre, a jump that is still considered a more masculine step. Jumping and move athletically are certainly accessible to women, so dancers in the 18th century challenged the expectations of their gender to achieve greater technical skill. Another dancer, Marie Salle, was one of the first woman choreographers in France. She pioneered costuming by electing to wear a robe based Greek statues in a performance of her self-choreographed ballet, Pygmalion. The robe was a more androgynous costuming piece than common costumes of the time. By wearing a more androgynous costume, Salle was perceived more masculinely, and thus as more legitimate dancer.