Les Ballets Russes

The Ballet Russes emerged in Paris in 1909. Sergei Diaghilev’s company quickly became central to Parisian culture through collaborations with other prominent artists (Picasso, Matisse, Prokofiev, Ravel, and Stravinsky).

Modern conceptions of queerness were just beginning. Doctor Magnus Hirschfeld was becoming relatively well known for his research on “intermediate sexual types.” As such, Diaghilev lived during a period where people were beginning to self-identify with queerness, although he didn’t identify as homosexual. Diaghilev was known to be romantically involved with male dancers in the company, although he didn’t identify as homosexual.

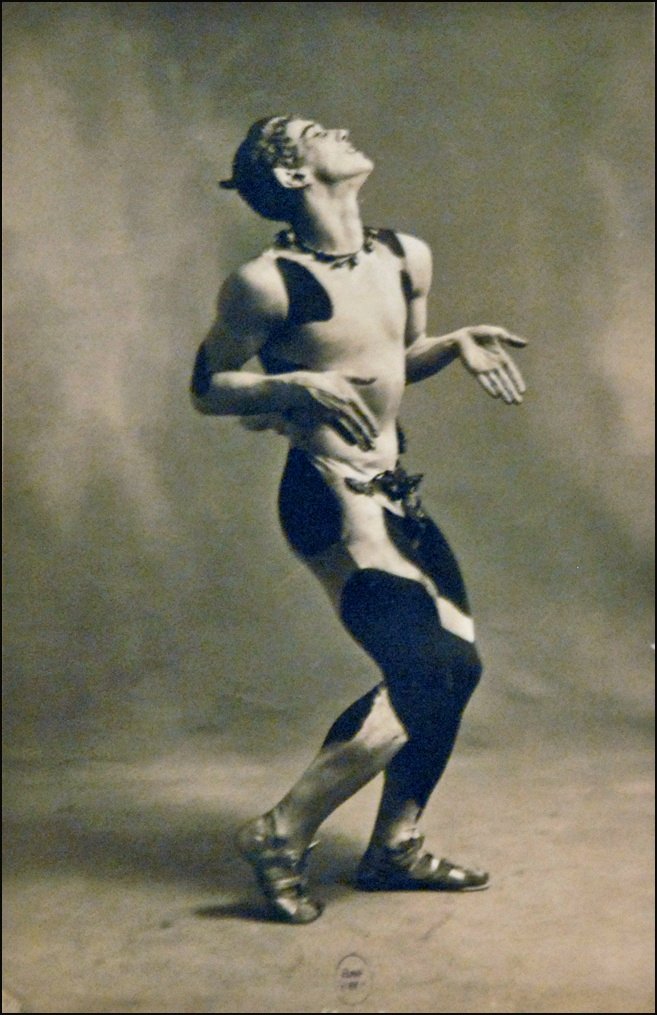

Diaghilev’s impact on ballet had undeniably queer undertones. Choreographers of the era were strategic in concealing queer “double meanings” in their work, a practice known as “queer coding.” One of the most famous examples of this is L’Apres-midi d’un faune. Choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky, the ballet’s protagonist is a faun, a common figure in homoerotica of the period. The Ballet Russes drew in a more eclectic crowd, including avant-garde artists and self-identified homosexuals. The Ballet Russes were uniquely positioned to create this more open space in ballet. At the time, due to rampant orientalism, Russia was not considered a civilized European nation by Western Europe. As such, the Ballet Russes were able to create work that would not have been as widely accepted if it were created or performed by French or other European artists.

Vaslav Nijinsky is a prime example of Russian “exoticness.” Nijinsky’s recorded sexual orientation is muddy at best. He was embroiled in a years-long relationship with Diaghilev, a regular visitor of female Parisian prostitutes, and ultimately married Romola de Pulszky in 1913, after which Diaghilev dismissed him from the Ballet Russes. Nijinsky’s performance represents a continuation of the tradition of androgyny-fueled stardom in ballet. His masculine technical ability and feminine quality led to blockbuster fame.

Ballet Comes to North America

In 1933, Lincoln Kirstein made the step that would cement ballet into American culture. Kirstein, from New York, had admired the Ballet Russes work from a young age and had traveled to Europe to see Diaghilev’s company. After Diaghilev’s death in 1929, Kirsten brought his final choreographer, George Balanchine, to New York to found a ballet school and company. Kirstein and Balanchine’s productions tended away from the Ballet Russes’ iconic modernism and towards asexual neoclassicism. However, indications of queerness did not altogether disappear under Kirstein’s leadership. He himself, as well as a number of his collaborators, had homosexual romantic relationships. American queer-coded ballets shifted towards a sense of hypermasculinity to disguise homosexual themes beneath notions of Americana.

Ballet’s “Coming Out”

The late 20th century saw a rise in visibility of LGBTQ+ Americans in and out of ballet. German dance critic Horst Koegler cites Jerome Robbins’ Events as the “first explicitly gay pas de deux”. The ballet premiered in 1961 at the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy. The ballet is not one of Robbins’ well-known or renowned works, but it marks the beginning of a slow shift in the explicit characterization of queerness in ballet. The timing of Events’ premier parallels the beginning of the queer liberation movements of the era. The 1960s saw a series of riots in retaliation to police raids of bars and other establishments frequented by queer communities, the most famous of which were the riots at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. As the visibility of queer people in North America grew, there was a significant uptick in ballet performances with explicitly queer themes and queer storylines. Les Ballets Trokadero de Monte Carlo began performances in 1974 and have sustained popularity for the past 50 years. Affectionately called “the Trocks,” the troupe performs classical ballet stories in drag and pays tribute to both camp queer culture and the glamorous Russian ballerinas of the early 20th century. In the early days, few dancers would take the risk of performing full-time with the Trocks, rather maintaining a day job at a classical ballet company and working with the Trocks on the side. However, their performances are often considered comedic and the company is not viewed as a classical ballet company. The Trocks’ association with comedy is not only derived from their over-the-top drag personas, but also from a trend of creating en pointe men’s roles for comedic characters in classical ballets.

Fredrick Ashton used this method from the 1940s-1960s in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Bottom), Cinderella (Ugly Stepsister), and La Fille Gardée (Mother Simone). These performances, as they were created in the later half of the 20th century and as they continue to be performed today, are colored by queerphobic rhetoric which dictates that the femininity of pointe work renders any male dancer who engages in it frivolous.

The 1980s and 90s saw attempts to create queer interpretations of classical ballets. Swan Lake, as one of the most iconic classical ballets ever choreographed, was a common subject of these efforts. Rudolf Nureyev’s 1984 production of Swan Lake positions Seigfried as a more central character. In this production, the young Seigfried is presented with the opportunity to select his fiancée from many suitable court ladies but instead maintains a close relationship with his male advisor and falls for Odette/Odile, a swan maiden of his own imagination. The climactic pas de deux of the original is transformed into a pas de trois including Seigfreid, Odile, and the advisor. As in the tradition of many decades of queer-coded ballets, Nureyev’s production leaves the queer interpretation of the work to the audience. Roughly a decade after Nureyev’s Swan Lake premiered, another, and perhaps the most iconic, queer Swan Lake emerged. Matthew Bourne’s 1995 production of Swan Lake has achieved worldwide fame and is often referred to as “the gay Swan Lake.” Bourne has been clear that the production was not meant to be interpreted that way. Nevertheless, a restaging of Swan Lake which includes an all-male corps de ballet playing the swans will introduce some element of queerness. The Swan (equivalent of Odette/Odile) and the Prince are both played by men. As such, the ballet manages to combine seriousness with play in gender while still distinctly breaking from cisheteronormativity.